My excellent friend Ken just sent me THIS, which is an article from the Huffington Post about Whitman’s poem “Year of Meteors.” Apparently a scientist has used Whitman’s poem, a painting by Church, and some New York newspapers to determine that Whitman actually witnessed a very rare meteroic event. I love this idea of two pieces of art leading to a scientific discovery. And I love the way the article and analysis are all about the scientific event rather than the poem’s more powerful cosmic explosions, homoerotic desire and poetry itself.

The brown-sugar shortbread I’m baking for my Whitmaniacs is in the oven, the freshman final exams I should be grading are stacked beside me, my children are sleeping all snug in their beds, and I am melancholy that tomorrow effectively disbands the Digital Whitman Fellowship. There is much work undone. By Friday morning the heaviest of those burdens will be grading final projects, but tonight it’s the realization that I’ve never really blogged about the Womanly Whitman. Since naming him in response to Dr. Earnhart’s famous James Bond Speech on our first night of class in August, God knows I’ve talked about him, I’ve watched students and two other professors at UMW pick up the term, I’ve mentioned him to Barbara Bair, the Library of Congress archivist who changed our semester. But he deserves one final huzzah here on I Give You My Hand.

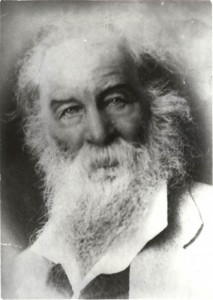

Before this project, I taught Whitman a lot, in three or four different courses, but had come to focus almost solely on “Song of Myself”– sometimes 1855, sometimes Deathbed, sometimes with humor, sometimes with aggravation, always with an appreciation for poetic genius, and always with a pretty clear picture in my head of the kind of guy I was dealing with: macho, swaggering, egotistical. You know, this guy:

The Enhanced Manly Whitman

Even his radical inclusion had begun to feel at best appropriative, at worst cannibalistic, consuming the American people to feed his vast, virile self. “Song of Myself” was like a poetic codpiece. I couldn’t see the forest for the fibres of manly wheat. You understand me.

I exaggerate, of course, but don’t entirely lie. During the re-immersion in Whitman that I undertook about a year ago, something happened. In between blaming Whitman for Charles Olson and rolling my eyes at his father-stuff, I began to see someone unexpected emerging–someone with soft hips and warm eyes, someone surprisingly quiet, a good listener, a bringer of lemons and ice cream, a moon-watcher. This person:

The Marriage Photo, with pleased smiles and fleshy hips

And this one:

This Whitman appeared in the memoirs of his friends, in letters to his mother, and, powerfully, in the Civil War writings to which I was turning fresh and focused attention. (To my surprise, when I went back to “Song of Myself,” of course this Whitman was all over it.) Right now my favorite work of this Whitman may be “Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night,” which is here.

“Vigil Strange” imagines a private wake for a young dead soldier, kept through the night by an older, grieving comrade. It is not a perfect poem, being marred by weird syntactic inversions and being, arguably, maudlin. But it is intensely moving in the quietness of its grief:

Till late in the night reliev’d to the place at last again I made my way,

Found you in death so cold dear comrade, found your body son of responding kisses, (never again on earth responding,)

and its acceptance of the unacceptable:

Passing sweet hours, immortal and mystic hours with you dearest comrade—not a tear, not a word,

Vigil of silence, love and death, vigil for you my son and my soldier,

As onward silently stars aloft, eastward new ones upward stole . . .

and in its exquisite, unbearable gentleness:

My comrade I wrapt in his blanket, envelop’d well his form,

Folded the blanket well, tucking it carefully over head and carefully under feet,

And there and then and bathed by the rising sun, my son in his grave, in his rude-dug grave I deposited. . .

“Vigil Strange” has a rhythm that approaches incantation or lullaby–long, frequently repetitive lines that are calming (cut short abrasively by the reality of war in the aborted rhythm of the final line/action: “And buried him where he fell”). The swaddling of the “son,” “my soldier,” in his blanket is, I’m going to suggest, not masculine, not even paternal. It is maternal, tender, womanly.

What problems arise from my assertion? A lot, and two of them have to be addressed. First, unquestionably my desire to call this voice the Womanly Whitman is rooted heavily in a construction of the womanly and the maternal that is traditional, nurturing, compassionate, the angel in the hospital ward. It is the construction I invoked in the domestic scene that began this post. It is a construction with which I am utterly at odds ideologically and which I have doggedly and sometimes fiercely interrogated in my teaching, my politics, and many of my life choices. Second, there is a complication in casting the speaker of “Vigil Strange” as maternal, a Freudian complication best indicated by the title from Lawrence (curse, growl): “Sons and Lovers.” My casting of this soldier as maternal effectively recontains the homoeroticism of the poem:

One look I but gave which your dear eyes return’d with a look I shall never forget,

One touch of your hand to mine O boy, reach’d up as you lay on the ground,

Then onward I sped in the battle, the even-contested battle,

Till late in the night reliev’d to the place at last again I made my way,

Found you in death so cold dear comrade, found your body son of responding kisses, (never again on earth responding,)

The language of “my son,” “dear eyes,” and “boy” can mask the power of that body, those kisses, the assertion of love that will transcend death (less so, perhaps, if you’ve read the repeated use of the word “son” in Whitman’s letters to his partner Peter Doyle). OR, and this is equally problematic, I am mapping “gay” over “tender, feminine, womanly” as though they are fundamentally interchangeable.

Oy vey. Now I’m really in the total animal soup of essentialism.

But I want that term. Maybe because in some ways it is MY “womanly”– that is to say, “womanly” is a tag not unlike the “myWW” tag I append to certain posts to indicate a connection to Whitman that goes beyond admiration of the poetic line, the image, the nest of guarded duplicate eggs you have to have to throw over the literary establishment. It is, I will say on safer ground, a non-patriarchal Whitman: tender, generous, nurturing, doubting, equalizing. It’s the Whitman this semester has given me, and I’m grateful.

Well, you all know I live in a house with a seemingly friendly but unsettled ghost. But let’s say that it’s gotten more crowded lately. Wednesday night my son called his dad into his room during the night– he said that he was scared of mean faces he thought he’d seen in the room but that he had clearly seen our ghost (not the first time by a long shot, but the first time as part of some larger narrative) and felt protected by it— and the clincher? He had seen the ghost of the aged Walt Whitman in his room, standing by our ghost and also protecting him. Whitmaniacs, dream on.

In thinking about Whitman’s legacy, I got curious about how much Modernist writers beyond Pound and Williams were engaging him– that is, how much he’d become a common name or referent in writing of the time. So I went to the awesome and ever-growing Modernist Journals Project to poke around. A search for “Walt Whitman” (used first name to screen out candy advertisements, but it probably limited my hits) yielded 111 references. In addition to the examples below, which represent just a fraction, reviews and advertisements for Traubel’s volumes, for a volume of Whitman’s letters with Anne Gilchrist, for publications of Leaves, etc. indicate an interest in Whitman as well. Throughout the magazines, Whitman is compared to Poe, to Lincoln, to Mallarme, to Swinburne, to Blake, etc. etc.

One of the most prominent uses of Whitman is that the journal Poetry, of central importance in the history of Modernism, from its very first issue in 1912 included this on its back cover:

To have great poets there must be great

audiences, too.—Whitman.

HELP us to give the art of poetry an organ in America. Help us to give the poets a chance to be heard in their own place, to offer us their best and most serious work instead of page-end poems squeezed in between miscellaneous articles and stories.

If you love good poetry, subscribe.

If you believe that this art, like painting, sculpture, music and architecture, requires and deserves public recognition and support,subscribe.

If you believe with Whitman that “the topmost proof of a race is its own born poetry,” subscribe.

Throughout various issues, the question of whether or not great poetry needs great audiences is actively taken up by Harriet Monroe, Poetry‘s editor, and Ezra Pound, who disagree about it. Eventually, by the start of Volume 2, the back cover uses only that quote by Whitman and dropped the rest of the text above.

By October 1915 in Poetry, a comment written by Alice Corbin Henderson, engaging with a critical letter written about the publication of Carl Sandburg in the magazine (ouch! take that, Mr. Hervey!), calls on Whitman as an elder statesman, a judge of all that is good in poetry:

“And, by the way, what, oh, what do you suppose Walt would have thought of Miss Monroe’s magazine if he had lived to see it?” So asks Mr. John L. Hervey in a recent letter to The Dial. The question is delightfully suggestive. We would love to know just what Walt Whitman would have thought of POETRY. It is not impossible that Mr. Hervey thinks that Walt would have thought of POETRY just what he, Mr. Hervey, thinks of the magazine. No doubt it is under this conviction that Mr. Hervey delivers this last, smashing blow! Still, there isn’t any way of being sure that Walt would have come out on Mr. Hervey’s side. Walt was very tolerant ; tolerant of poets—you remember his charming, “I like your tinkle, Tom,” to Thomas Bailey Aldrich ; also tolerant of editors—of Richard Watson Gilder, to whom Whitman’s November Boughs “did not appeal” for publication in The Century.

No, it’s a toss-up just what Walt would have thought about the magazine. Undoubtedly, he would have thought about it just as each of you, whoever you are, now reading this magazine, think about it. For the great dead, curiously enough, always mold their opinions to suit their admirers. . . . And now Mr. Hervey wants Miss Monroe to say what Carl Sandburg’s poems will mean to the reader of fifty years hence, if she thinks any of them will live that long. Mr. Hervey himself does not risk a direct opinion. Fortunately there were people intelligent and courageous enough to risk an opinion on Whitman fifty years ago. And these people were not the editors of magazines, who “knew what the people wanted,” and took no risks. If Whitman had waited for them, Mr. Hervey might have missed his Walt, and he would then have had to invoke some other shadowy figure . . . to pass mythical judgment upon the new poetry. . . . Would Walt applaud the risk taken by Miss Monroe in publishing it, or would he, too, like Mr. Hervey, be shocked by her temerity?

In volume 1.3 of Poetry (1912), this discussion of Whitman’s continental influence is given:

It is significant of American tardiness in the development of a national literary tradition that the name of Walt Whitman is today a greater influence with the young writers of the continent than with our own. Not since France discovered Poe has literary Europe been so moved by anything American. The suggestion has even been made that ‘Whitmanism’ is rapidly to supersede ‘Nietzscheism’ as the dominant factor in modern thought. Léon Bazalgette translated Leaves of Grass into French in 1908. A school of followers of the Whitman philosophy and style was an almost immediate consequence. Such of the leading reviews as sympathize at all with the strong ‘young’ movement to break the shackles of classicism which have so long bound French prosody to the heroic couplet, the sonnet, and the alexandrine, are publishing not only articles on ‘Whitmanism’ as a movement, but numbers of poems in the new flexible chanting rhythms.

In the second volume of BLAST, a Vorticist journal edited by Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis, a column entitled AMERICAN ART contains the following:

American art, when it comes, will be Mongol, inhuman,optimistic, and very much on the precious side, as opposed to European pathos and solidity.

Wait Whitman Bland and easy braggart of a very cosmic self. He lies, salmon-coloured and serene, whitling a stick in a very eerie dawn, oceanic emotion handy at his elbow.

What?! BLAST also describes a book as having “a soul like Walt Whitman, but none of the hirsute mistakes of that personage, and invention instead of sensibility” (!).

Whitman appears comparatively in book reviews, as in this one on D.H. Lawrence (authorial commentary: boo Lawrence): “‘Leaves of Grass ‘ rise to one’s mind as this fine catalogue is proclaimed; it seems to me now that Walt Whitman’s poetry is the only proper parallel to Mr. Lawrence’s ‘Sons and Lovers'” (The Blue Review 1.3).

Whitman is referenced repeatedly as a thinker moreso than poet in The New Age, a publication which describes itself as “an independent socialist review of politics, literature and art” or, eventually, “a weekly review of politics, literature and art” (examples just below from issues in 1907):

The dominant idea of Whitman, for example, is undeniably friendship, or what he calls camaraderie ; and the fact that the early Socialists called each other Comrade without distinction of sex is Significant.

This example, from a book review of a collection by Edward Carpenter, is bound to make Brendon as mad as it made me:

The politicians may make Socialism ; but such a spirit as Carpenter’s is required to make Socialists. I remember making in a moment of dubious inspiration an epithet for Carpenter that appeared to me at the time essentially true. I called him Mrs. Whitman. Whitman certainly impressed one with the sense of masculinity ; and equally certainly there are qualities in Carpenter that strike one as womanly.

In February 1910, a writer laments the shaky condition of American letters:

Nothing mortified me so much as to be told by an Englishman that Europe absorbs our finest talent. I was angry. He then began to call the names–Whistler, Sargent, Shannon, Abbey, Henry James, Henry Harland, and others of whom I had never heard. He named so many I cannot recall them. He wound up by saying Walt Whitman would have been far happier had he lived in England where he would have had a public instead of a small coterie in his own country. Needless to say my anger gave place to shame and mortification.

In November 1915, The New Age reprints this part of a review of a translation of Whitman (as an example of an ass’s bray):

To him all is without exceptions just as in prostitution to him all men are “friends,” just as to the prostitute everyone is a guest. Pah ! Pah ! What blindness! Whitman is blind and deaf, for he does not distinguish and, therefore, does not select, neither colours nor sounds nor persons. And the human soul?–he has no comprehension of it.

We too beg, of course, to disagree.

I can’t believe I forgot to scan this, but check it out:

“A Pact”

by Ezra Pound

I make a pact with you, Walt Whitman –

I have detested you long enough.

I come to you as a grown child

Who has had a pig-headed father;

I am old enough now to make friends.

It was you that broke the new wood,

Now is a time for carving.

We have one sap and one root –

Let there be commerce between us.

John Burroughs in a letter about Whitman, 1864:

He bathed today while I was there–such a handsome body, and such delicate rosy flesh I never saw before. I told him he looked good enough to eat, which, he said, he should consider a poor recommendation if he were among the cannibals.

My reaction to our reading this week has been so mixed– in some ways, I feel a sense of closure, of finality as we focus on the last edition and the last days. That reflects, I think, the personal, human Whitman we have gotten attached to this semester, since obviously as a literature professor I must have an unshakeable faith in the power of the work to outlive its maker and its time . . . right? his work doesn’t reach closure because his body does. But it doesn’t feel like it today. Instead, my sense that with Whitman’s “death” (felt like checking the obits this a.m.) comes an unbreachable divide makes me frantic… don’t die now, Walt Whitman! I have a lot left to read, to learn, to blog! It’s too soon for me! Maybe I am responding to the waning days of Digital Whitman more than the loss of Walt Whitman, but it’s crazy how those have become hard to separate lately.

Well, I include here something I found in our old friend Reynolds, a bit of letter WW sent with an advance copy of the deathbed edition on December 6, 1891 (intertextual note: 11 days before he took the “severe chill” that Longaker says marks “the invasion of the fatal sickness”):

L. of G. at last complete—after 33 y’rs of hackling at it, all times & moods of my life, fair weather & foul, all parts of the land, and peace & war, young & old—

O Whitman, Our Whitman (image from ExplorePAHistory.com)

“Get Well Soon :)”

Once steady hands now faltering from your fall,

this hand that penned mountains, sung through ferry waters, hewn rough earth boys, their bodies taken by war as your body has taken you.

You, the kosmos, can not be taken by such human failings.

Calamus cane in hand, stand erect, your perpetual journey is still left to tramp.

Your America is orphaned without your voice, your body; without your arms to encircle her.

You shall yet whisper your secrets in my ear, leaning on my shoulder should you need it.

Comrade, let me now take your hand and show you what you have shown me.

—Jessica and Erin

“Rise o Dancers from your Courtyard Plaza”

Rise o dancers from your courtyard plaza, till you stomping, snapping, spin,

Sidelong my eyes devoured what your practice gave me,

Long I roamed the streets of DC, long I watched the rain pouring,

I traveled Walt Whitman Way and slept in the seats of Ford’s Theatre, I crossed the streets, I jumped the puddles,

I descended to the secret tunnel and sail’d out to the Metro,

I sailed through the storm, I was soaked by the storm,

I watched with joy Chelsea threatening Sam

I mark’d the water lines where puddles splashed so high,

I heard the wind piping, I saw the black clouds,

Saw from afar what thrilled and moonwalked (O hilarious! O ridiculous as my heart, and

corny!)

Heard the continuous beat as it bellowed over the car horns.

—Brendon and Sam K.

“O Wondrous Washington!”

O wondrous Washington!

City of rain and wind,

You drench us in amorous drops;

Our limbs move weary in recycled steps—

O wretched limbs!

Let us deliciously journey

And see your scribbled ink,

And feel the buzz of your presence,

And read the immortal words,

And rattle our frames with splendid, tattered images,

And depart limp and satiated.

O to find you and taste fully of your knowledge!

Wet lips, wet shoes, wet hair—

Wondrous, enriched fatigue.

–Allison and Sarah

On Sunken Road I heard the calls of soldiers past—

O, Sergeant Richard Kirkland, you cradle one, my brother comrade, I could have sworn you were an angel watching me from your periphery, adoring.

It being the real, still-standing portion of the wall, I imagine the sons of the nation, and also the daughters, facing each other, their hearts join’d as joints of a wall by perforation;

Limbs erect as the rifles readied by their masters to unroot the Calamus,

I walk’d the gravel path with Kirkland, Lee, Whitman—fearless of intolerant rebels who might flank the figures of my mind:

White opposition approaches—a different union entire.

—Meghan, Virginia, and Natalie

I sing the now-pav’d road which underneath my soles spanned the nubbed monument to the beds of delicate soldiers,

Where my callous hands soothed wounds from a war of brother against brother,

The road, infinite, wandering past Georgetown and the Potomac and the garbage eating pigs

And the mud and Andrew Jackson airing laundry and the doors of Saint John’s church looking out onto the White Mansion and the canals, and the old warriors walking five stories for one month’s check, and the theatre where my brother, my comrade, fell and spoke no more

Oh road now pav’d over blood! Pav’d over me! I trod your streets once known in dirt

you conceal me, can I learn your roads once more?

—Chelsea and Ben